This article orginally appeared in The Conversation and was republished by the National Post.

Canada’s future prosperity will depend on effective environmental conservation and sustainable — and profitable — agriculture. Unfortunately, recent comments from former Saskatchewan premier Brad Wall pit the two concerns against each other unnecessarily.

Agriculture and the environment are not mutually exclusive, and polarization of the issues only undermines progress toward successful and sustainable solutions.

A major fault line among agricultural and environmental concerns has long been the question of whether food production and wild spaces can coexist. Do wild lands need to be set aside to compensate for the impacts of agriculture? Or can agriculture be practised in a way that is compatible with biodiversity?

This “land sparing” versus “land sharing” debate has hindered progress, and a large body of research suggests that the dichotomy is false.

Sustainable agriculture

Agriculture and biodiversity are more closely interdependent than we realize. Ecological approaches to agriculture, which seek to build soil, manage beneficial plants and insects and mimic natural cycles can also promote conservation outcomes, help address global climate change and improve farmer livelihoods, as well as a variety of other socially desired outcomes.

Given the food needs of Canada and the world’s large and growing population, food production strategies that don’t work with biodiversity are, at best, a missed opportunity. At worst, they are an unmet responsibility to Canadians and the world.

For example, both farmers and conservation biologists need pollinators, but honeybees and other wild pollinators are in decline. If we are to avoid long-term impacts on food production and ecosystems across North America, we must take immediate action to reverse the downturn.

Zero-sum game

In his comments, Wall refers to the environmental opposition to oil sands development, and warns of environmentalists similarly seeking to paint agriculture as “dirty.” This rhetoric serves only to further escalate an already tense conflict, reinforcing an us-versus-them mentality.

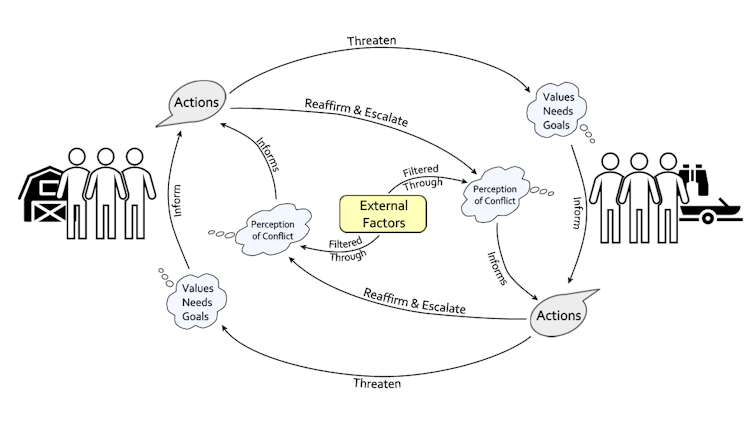

Individuals on different sides of a conflict often share many values. Despite being locked into a years-long conflict over salmon, commercial, sport and subsistence fishers in Alaska often agreed on what mattered, including identity, family, tradition and benefit to the local community. Only when conflict escalates do groups begin to lose touch with one another, responding more to rumours and caricatures than to people’s intentions and values.

Fuelling conflict with rhetoric is particularly troublesome in Saskatchewan, where there are ongoing conflicts over agricultural drainage. Drainage describes the removal of water to increase the land available for agricultural production. Drainage is important to agriculture in the prairies, but it can also have negative impacts on wetlands and increase downstream flood risk.

Our research looks at how people are trying to make better decisions about prairie drainage. We have already seen how conflict is undermining trust in new processes for permitting. Drainage, like other environmental issues facing society, is a complex issue; regardless of one’s perceptions regarding the province’s current approach, only through earnest collaboration can we find mutually agreeable and sustainable strategies.

Managing conflict

Conflict escalation makes the gap between people’s perspectives seem larger and more irreconcilable than it is. In our work we regularly encounter farmers who hold strong environmental values. There are many success stories where farmers and environmentalists have worked together to find mutually agreeable solutions.

In the Malpai Borderlands of New Mexico, for example, ranchers and environmentalists have worked together for three decades to manage nearly one million acres of range lands that are crucial to local wildlife and local ranching livelihoods. Similarly, farmers, managers and residents of Perham, Minn., stopped pointing fingers and started working together to solve water quality issues related to agricultural runoff.

What’s key in these and other cases is that people take the time to understand each other’s baselines, world views and deepest concerns.

Stoking conflict, however, only serves to keep people from seeing the issue as a shared problem. One only needs to look at the political polarization in the United States to see how troublesome conflict escalation can be.

Sustainable, mutually beneficial futures

Canada’s agricultural sector is undergoing dramatic transformations. Climate change and other challenges are motivating many producers to rethink how they produce food. Similarly, the world of environmental conservation is changing, with First Nations, for example, leading the development of new approaches to stewardship of working landscapes.

Issues like climate change require rapid transformations in both conservation and food production practices. Rather than perpetuating polarization, bold leadership should work toward consensus among groups. This must start with recognizing that food production and conservation are not opposing ends of the spectrum.

There are many ways to move beyond these disputes, but people must be willing to take a leap of faith. Finger-pointing and stoking conflict, while perhaps politically expedient for some, takes any real progress off the table.![]()