U of G scientists have made a discovery that could reduce the spread of tumours by hindering a protein that binds cancer cells together and allows them to invade tissues.

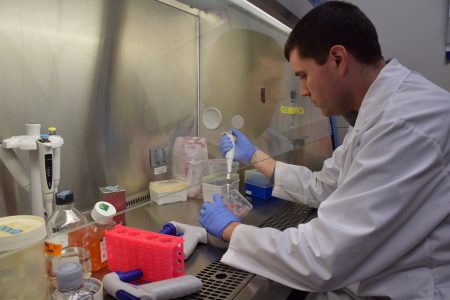

The groundbreaking study identified a protein, known as cadherin-22, as a potential factor in cancer metastasis, or spreading, and showed that hindering it decreased the adhesion and invasion rate of breast and brain cancer cells by up to 90 per cent.

“Cadherin-22 could be a powerful prognostic marker for advanced cancer stages and patient outcomes,” said lead author Prof. Jim Uniacke, Department of Molecular and Cellular Biology. “If you can find a treatment or a drug that can block cadherin-22, you could potentially prevent cancer cells from moving, invading and metastasizing.”

Published in the journal Oncogene, the study looks specifically at hypoxia – low-oxygen conditions – in tumours.

Most solid cancer tumours that have outgrown their blood supply, and are therefore deprived of oxygen, are difficult to treat, and the cells within are capable of spreading rapidly and doing the most damage. In more than 100 breast and brain cancer patient tumour specimens, researchers found that the more hypoxic the tumour was, the more cadherin-22 it contained.

Until now, little was known about how oxygen-deprived cancer cells bound together and interacted to spread. The U of G researchers found that it is precisely under conditions of low oxygen that cancer cells trigger the production of cadherin-22, putting in motion a kind of protein boost that helps bind cells together, enhancing cellular movement, invasion and likely metastasis.

Until now, little was known about how oxygen-deprived cancer cells bound together and interacted to spread. The U of G researchers found that it is precisely under conditions of low oxygen that cancer cells trigger the production of cadherin-22, putting in motion a kind of protein boost that helps bind cells together, enhancing cellular movement, invasion and likely metastasis.

Cadherin-22 is located on cell surfaces, allowing hypoxic cancer cells to stick together and migrate collectively as a group, said Uniacke.

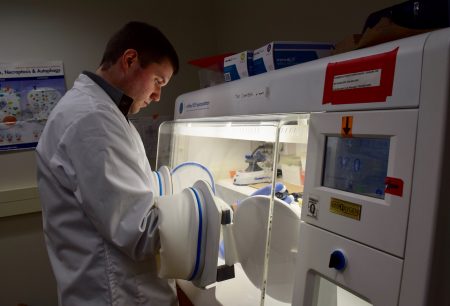

Scientists have known for decades that hypoxia plays a part in tumour growth metastasis and poor patient outcome. Studying breast and brain cancer cells in a hypoxia incubator, Uniacke and his team discovered that cadherin-22 is involved in this process to enable the spread of cancer cells.

“We found that the more hypoxic a tumour was, the more cadherin-22 there was in the area of the hypoxia,” he said. “Not only that, but the more cadherin-22 that there is in a tumour, the more advanced the cancer stage and the worse the prognosis is for the patients.”

For both cancer types, the research team used molecular tools to reduce the amount of cadherin-22. They placed the human cancer cells into the incubator and lowered the oxygen to a level comparable to that in a tumour. The cells failed to spread.

For both cancer types, the research team used molecular tools to reduce the amount of cadherin-22. They placed the human cancer cells into the incubator and lowered the oxygen to a level comparable to that in a tumour. The cells failed to spread.

“One very powerful and common tool in cell and molecular biology labs is, you can remove a protein from a cell and see how that cell behaves without it,” Uniacke said. “We culture our cancer cells in this very low-oxygen environment, and they start behaving like they are inside a low-oxygen tumour.”

The findings offer vital insights into how tumour cells could become aggressive and spread to other parts of the body.

“Because a cancer tumour has a poor blood supply, it doesn’t get the proper oxygen,” Uniacke said. “The cancerous cells need to change their behaviour, changing what proteins they synthesize in order to try to adapt to these environments.”

Higher levels of hypoxia in a tumour are strongly linked to poor survival rates in cancer patients, he said, and hypoxic tumours are often resistant to treatment.

This past May, Uniacke’s four-year study on low-oxygen tumour regions received $688,500 from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research.

Contact:

Prof. Jim Uniacke

juniacke@uoguelph.ca