A breakdown product of modern refrigerants that replaced banned ozone-depleting coolants will likely not threaten future generations, according to new University of Guelph research.

The study, published recently in the Journal of Toxicology and Environmental Health – B, found that trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) is extremely persistent in the environment and ultimately ends up in water, mostly in the oceans. The compound is not overly toxic and poses no risk of moving through the food chain, according to the study.

Still, study author Keith Solomon, an emeritus professor in U of G’s School of Environmental Sciences, says TFA requires monitoring because of its pervasiveness and persistence.

“What we showed in that study is that, first of all, TFA wasn’t very toxic, which is good news, but it didn’t seem to degrade at all,” he said.

TFA has an estimated half-life of 50,000 years. “It doesn’t go away,” said Solomon, who studies environmental toxicology and sits on a United Nations panel on the environmental effects of ozone depletion.

“TFA has rewritten the book on persistence. It’s like an element that you can’t destroy.”

The substance is produced naturally — apparently from undersea volcanic vents — and current ocean concentrations are about 200 nanograms per litre (a nanogram is one-billionth of a gram).

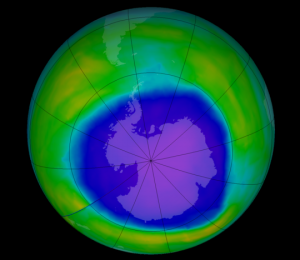

Studies of stratospheric ozone began in the 1930s but became a priority in 1987 following the enactment of the Vienna Convention’s Montreal Protocol, an international treaty designed to phase out the production of substances that deplete the ozone layer.

Solomon says stratospheric ozone earlier was degrading from the accidental release of refrigerants and the use of aerosol products and other chemicals. The ozone layer has healed, which he suggests is the first large-scale example of human intervention to repair environmental damage. The Montreal Protocol banned the use of older refrigerants and aerosol propellants.

New refrigerants, Solomon said, do not reach the stratosphere and break down quickly in the lower atmosphere.

“They are broken down by the great cleaner of the atmosphere — hydroxyl radical, which, funnily enough, is generated by ultraviolet (rays),” he said.

“Hydroxyl radicals react with and cause all sorts of air pollutants to degrade, so they clean the atmosphere. They actually allow us to survive on this planet. If it wasn’t for them, we wouldn’t exist.”

These modern refrigerants break down into non-toxic TFA. Solomon says a large majority of these chemicals are banned, and scientists know about those chemicals still in use. But many more chemicals could break down into TFA.

What needs monitoring, he said, are the 1.3 million other chemicals, pesticides and drugs worldwide that contain the trifluoromethyl group. Prozac is one of the most widely prescribed antidepressants available – and it could produce TFA when it is degraded.

“We know nothing about quantities, really,” he said. “We have some local data for the United States, but for global use and the release of these other chemicals, there is no data at all.”

The chemical accumulates in water but is unlikely to cause problems in future, he said. “The good news is that it won’t happen in our lifetime, or in our children’s lifetime; however, we still need to be vigilant.”