They’re long, skinny and slimy, with a mouth full of teeth and a raspy tongue for sucking on their prey. Sea lampreys are typically found along the coasts of the Atlantic Ocean and now they’re in the Great Lakes. First discovered in the lakes more than a century ago, their numbers are growing while fish stocks are dwindling.

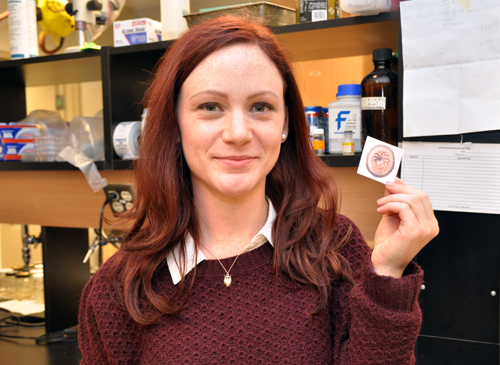

“They’re not a very nice fish,” says master’s student Adrienne McLean, who is studying the behaviour of sea lampreys to find better ways of trapping them. Her adviser is integrative biology professor Rob McLaughlin.

The eel-like creatures can grow up to 60 cm long, latching onto their prey with their round mouths and concentric circles of teeth. Once attached to a fish, sea lampreys suck their blood and other bodily fluids until the fish dies. Even if the fish survives a sea lamprey attack (only one in seven fish do), the large wounds left behind often become infected, causing death.

A sea lamprey can kill up to 18 kg of fish annually, according to the federal Department of Fisheries and Oceans (DFO). “They’re really good at killing fish,” says McLean, pointing to the decline of lake trout. Recreational and commercial fishers don’t want to catch wounded or dying fish, she adds, but the DFO offers a bounty for sea lampreys.

Current methods of controlling sea lampreys include the use of lampricide, which kills them at the larval stage, but it’s expensive and loses its efficacy once it’s flushed downstream. “For the money, it doesn’t make sense to use that for long-term management in large rivers,” she says.

Barriers can help keep adult sea lampreys from swimming upstream to spawn, but they can’t be used on large rivers or shipping channels. Electro-shocking is another population control method, but it also kills other fish.

Sea lampreys only breed once in their lifetime, says McLean, so if they’re prevented from spawning, that could help reduce their population. “They put all their energy toward reproduction once they hit adulthood,” she says, adding that even their digestive tract shrinks to accommodate more eggs. “Their body cavity is filled with eggs. They’re just like egg balloons.”

Trapping has been largely unsuccessful, says McLean, “so we want to find ways to increase trapping success, but we first need to understand why it’s low.” She studied the behaviour of sea lampreys around trap openings in the St. Marys River and found individual differences: some of them would stick their heads in the traps and then swim away, while others swam all the way in and became trapped. She thinks these behavioural differences could be passed on from one generation to the next.

McLean says recent studies of other species suggest that one animal may differ from others in its vulnerability to trapping even though they come from the same population. “This hasn’t been tested in aquatic invasive vertebrate species,” she adds.

In her master’s research, McLean found that the likelihood of a sea lamprey swimming into a trap depends on how long it lingers near the trap opening. The more time they spend there, the more likely they are to become trapped. “Hopefully we can use this to exploit their behaviour.”

Researchers are looking at designing traps with a ladder-like ramp for the sea lampreys to climb instead of the current funnel-entry traps.

“They’re actually a delicacy in Europe,” says McLean, adding that you probably wouldn’t want to eat a sea lamprey from the Great Lakes because they feed at the top of the food chain, which can cause toxins to accumulate in their bodies from their prey.

It’s believed that sea lampreys arrived in the Great Lakes aboard shipping vessels and spread through the expansion of shipping channels. They can live in both salt and fresh water.

During her undergrad, McLean studied the spiny water flea, another invasive species.