By Joey Sabljic, BA ’12, a former student writer with SPARK (Students Promoting Awareness of Research Knowledge)

Timing is everything, especially when contamination of food with Listeria bacteria is suspected. Public health and food inspection agencies need to act quickly, and knowing what kind of Listeria they’re dealing with helps protect Ontario consumers by stopping outbreaks at the source.

The current standard method, pulsed-field gel electrophoresis, is effective in bacterial strain tracking but can be cumbersome because of time limitations. There is a need for a faster method of developing molecular fingerprints.

That’s why scientists at U of G’s Agriculture and Food Laboratory (AFL) are creating a cost-effective Listeria strain characterization tool and database that will allow food and health agencies to quickly and accurately identify and track specific Listeria strains in the event of contamination or an outbreak.

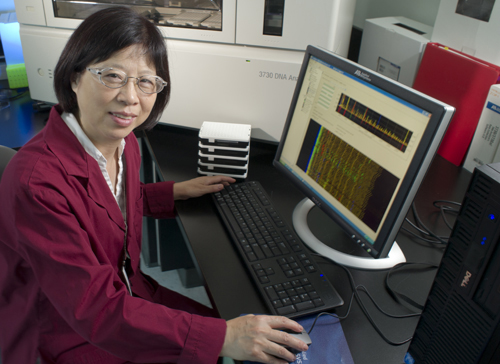

Shu Chen, a senior scientist and manager at the laboratory, is leading a research team to develop a multiple-locus variable-number tandem-repeat analysis (MLVA) methodology and database for Listeria monocytogenes. The MLVA database is similar to a criminal fingerprint database, except that it catalogues, tracks and identifies the strains of the roughly 2,500 L. monocytogenes isolates that have been collected at AFL over the past 15 years through partnership programs with the Ontario Ministry of Agriculture and Food (OMAF) and other testing programs.

“We’re trying to create a more proactive approach to Listeria testing,” says Chen. “We shouldn’t be waiting until after an outbreak has already happened to know which strain of Listeria we’re handling.”

She and her colleagues obtain Listeria isolates from samples from industry partners or government agencies such as OMAF and the Public Health Agency of Canada; they also receive Listeria isolates from Public Health Ontario and Health Canada. From there, using a technique called polymerase chain reaction, they generate an MLVA fingerprint for each isolate.

This technique allows a researcher to analyze multiple well-defined regions within each Listeria strain’s genetic code to determine its genotype.

Once they’ve analyzed the Listeria strain, an MLVA string number, similar to a barcode, is calculated and used to assign its genotype. This string number and relevant information such as the type of food product, swab or sample the isolate was obtained from are entered into the database.

Chen and her AFL team plan to make the MLVA methodology and database available for use by related government agencies. Each agency’s lab will be able to use the tool to analyze Listeria isolates and add the MLVA information to the database.

“We want to build a cross-laboratory network that will contribute to and strengthen the database on an immediate, real-time basis,” says Chen.

This MLVA tool will allow food inspection and public health agencies to quickly and easily identify the subtle differences between Listeria strains. It will also help Chen’s team and others identify the source of a Listeria infection or outbreak.

Collaborating agencies are OMAF, Public Health Ontario, Health Canada, the Public Health Agency of Canada, the Canadian Food Inspection Agency and the Ontario Ministry of the Environment. AFL is funded through the OMAF-U of G Partnership.