A new review paper on greening Alberta’s oil sands marks the fourth time in six years that the same U of G environmental microbiology course has turned various U of G grad students into co-authors in international journals.

Helping students learn to research and write a publishable paper – and see their efforts all the way into reputable publications – is the goal of the “Environmental Microbial Technology” graduate course offered in the winter semester.

Learning about microbiology and the environment is only partly the point, says Prof. Jack Trevors, School of Environmental Sciences. More important, he says, future researchers need to learn skills in identifying and solving research problems, communication, teamwork, leadership, critical thinking and writing.

“For the rest of their careers, this is what they’re going to have to do. If they don’t learn it in grad school, where are they going to learn it?” says Trevors, who is also a prolific contributor and editor for science journals.

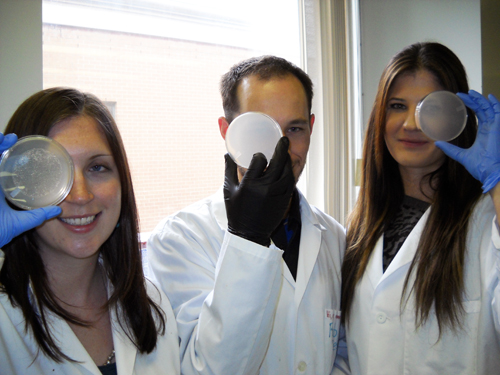

The paper by this year’s team appeared online in the October issue of the Journal of Industrial Microbiology and Biotechnology, published by the Society for Industrial Microbiology. Co-authors with Trevors were Karen Thompson and Nicole Harner, both PhD students, and master’s candidates Robert Best, Anna Best (no relation) and Terri Richardson.

Their paper recommends using bacteria adapted to extreme conditions – lots of oil, little water – to help plumb Canada’s oil sands.

Oil companies use major extraction methods, notably drilling and water injection, to pull oil from the ground. But those methods may leave more than two-thirds of the resource as residual oil that is too costly and difficult to remove.

To make that remaining oil easier to move, companies can use chemicals, gases and steam in enhanced oil recovery. Microbial enhanced oil recovery (MEOR) harnesses bacteria to make biofilms and surfactants that more easily flush oil.

These enhanced processes are already used in conventional wells. But the student researchers found few studies on using MEOR in the oil sands.

Various species adapted to the oil sands have already learned to make their own surfactants to survive under high oil and low water. That ability might be harnessed by oil companies, says Thompson: “Oil would separate better so less water would need to be pumped in.”

Besides reducing water use and pollution, this recovery method might help lower greenhouse gases from conventional oil sands extraction.

Oil companies need to consider piggybacking on natural processes, says Robert Best. “Nature’s the greatest innovator of different types of technology.”

The graduate course challenged students to consider the broader question of how life might survive with little water. Trevors advised them on how to find and research a topic and prepare a journal submission.

In 2005, a group paper about microbial gene expression in soil appeared in the Journal of Microbiological Methods. Two student papers were published in 2009 in Antonie van Leeuwenhoek and the World Journal of Microbial Biotechnology.

In any semester, up to six students have taken the course and co-authored a paper, often marking their first journal publication. Says Best: “Learning the process of getting a paper published is invaluable.”