Five years of social science research in Canada’s Arctic has taught one University of Guelph geography professor a thing or two about climate change’s “human face.”

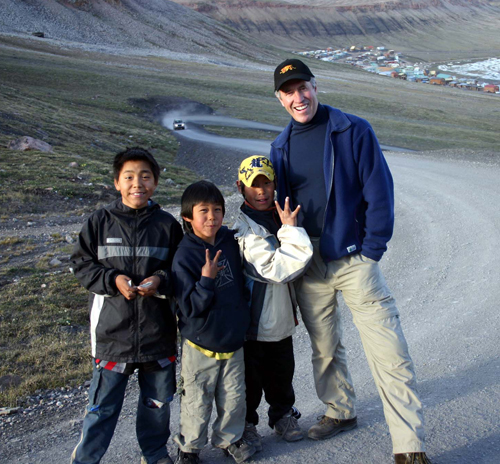

Prof. Barry Smit is the Canada Research Chair in Global Environmental Change, and since 2005 he’s studied how Arctic communities have tried to adapt to the rising temperatures caused by major shifts in global weather patterns.

The human dimension of climate change has long been understudied, says Smit. During two research projects — one with ArcticNet and another with the International Polar Year project — Smit has seen first-hand how Canada’s Inuit have dealt with changing ice levels, wind speed, migration routes and other factors.

“It’s already affecting the people who live there,” says Smit about the impact of global warming.

“And they’re having to figure out ways of adapting their livelihoods to face the changes caused by these changing conditions.”

Some communities are seeing their dietary patterns evolve because the animals they’ve traditionally hunted have shifted their migratory patterns, says Smit. That shift has caused those communities to rely on grocery stores for their food – and since the groceries found in Canada’s Arctic are often no better than “what we in the south would generally characterize as junk food,” that’s led to teeth problems and higher rates of diabetes, says Smit.

Part of the goal of his research is to challenge the idea that physical and social environments are completely unrelated. That’s certainly not true, he says, if you look at how many Inuit relate to the ice they live on.

“The ice is their highway. And one of the thing they’ve noticed is that their highway is collapsing in places it’s never collapsed before,” he says.

Smit is also the director of the Canadian Climate Impacts and Adaptation Research Network and a member of the scientific advisory committee on the United Nations Environment Program. His work has involved partnerships not only with researchers from other Arctic countries but also with stakeholders in the communities themselves.

His team’s research, he says, has been incorporated into the communities’ day-to-day decision-making — in the setting of hunting quotas, for instance, or in the construction of buildings on the melting permafrost.

And he points out that the research isn’t just a one-way flow in which his team bestows its wisdom upon the Arctic communities. Instead, the Inuit communities have helped refine his own research – by pointing out, for example, that it’s not so much the warmer temperatures that create the most significant social problems but the changing winds that move the ice to places it’s never been before.

Smit has also been involved with similar research into the relationship between social and environmental outcomes in Chile and Ghana. He adds that he’s working on a co-operative project with researchers and community members in the South Pacific and on Haida Gwaii off the coast of British Columbia to study the social impact of rising ocean levels.

All that work, he says, is concerned with bringing about a more “holistic analysis” of climate change. “The human face of climate change isn’t often recognized.”

By Ryan Saxby Hill

Canadian Federation for the Humanities and Social Sciences

Editor’s Note: Geography professor Barry Smit was invited to take part in a 10th-anniversary celebration of the Canada Research Chairs (CRC) this week in Toronto. The Canadian Federation for the Humanities and Social Sciences selected Smit as one of the CRCs to highlight during the event.