What do you do with the knowledge you’ve created or discovered during your time at U of G? You can save it in the University’s archive for knowledge information called “the Atrium.” But you won’t find the repository on any campus maps. Instead it’s a virtual storage space found at http://atrium.lib.uoguelph.ca.

“The Atrium is designed to bring together all the creative work and intellectual capital of the University,” says Jane Burpee, associate librarian, research and scholarly communications. “We are committed to the preservation and curation of these items.”

Items are not only indexed in the library website but are accessible to others through Google or Google Scholar searches.

We hope that sometime soon, all graduate students will be required to deposit their theses and dissertations into the Atrium. “Because these will be accessible through online searches, it will give the students much higher visibility,” says Burpee.

The Atrium’s collection is already quite eclectic. Images from OVC’s veterinary records and paintings of nudes live side-by-side in this virtual home with scientific articles and materials. As it expands, the scope will broaden.

Jonathan Newman, director of the School of Environmental Sciences, created a set of guidelines last year to encourage faculty and students in the school to archive their works in the Atrium. He’d also like to have raw data archived.

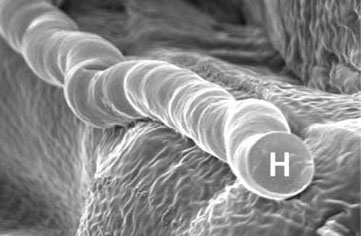

“For example, we have long-term weather data collected at the Elora Research Station and the Guelph Turfgrass Institute. We also have a collection of photos of thin-cut sections of soil that have been injected with resin to make the various elements visible,” says Newman. “I think preserving these data is important. If the person who has the thin-cut sections stored is hit by a bus tomorrow, these data may largely be lost.”

The organization and structure of the Atrium is also helpful for increasing access to research, something Burpee is enthusiastic about.

“Open access is a global, world-wide movement,” she says. “Open access means that scientific literature and research is available online, free of charge, so that it can be searched and studied.”

This is valuable, she adds, because “science is based on the exchange of ideas,” and some schools, especially those in poorer countries, may not have access to the costly databases needed to access material published in many journals. “Even the most prestigious institutions are struggling to purchase all the journals and resources that their students and researchers need,” says Burpee.

Newman separates these two issues: “I think that even for those who do not want to be involved in open access, there is value in the archiving of materials.”

Some other universities, including Harvard, York and Athabasca, have policies requiring faculty and students to put certain materials into the collection. “Since much research is funded by government, in many parts of the world, funders are requiring, as part of the grant process, that the researcher explain how the study will be archived and made accessible,” he explains. “Data collected for one purpose may be valuable for many others and shouldn’t be wasted.”

In some fields the most prestigious journals restrict or prohibit the writers of articles they publish from allowing open access, but this is changing. “The growth of public access journals over the past eight years has been dramatic,” Newman says.

He’s pleased that U of G has taken these steps to create the Atrium and make the process of submitting materials straightforward. Now it’s up to University staff, faculty and students to keep sending in their work.

“It needs to become a habit,” Newman says, “so that when your paper is published, you don’t just update your CV, you also have it deposited in the Atrium.”