Donald Shaver was a 12-year-old schoolboy during the Depression when he began feeding the world. Not that he would have described his plans then in such grand terms.

It was something closer to his heart that prompted him to raise chickens in handmade hen houses in a vacant lot next to his childhood home in Galt, now part of Cambridge, Ont. “I always loved baby chicks,” says Shaver.

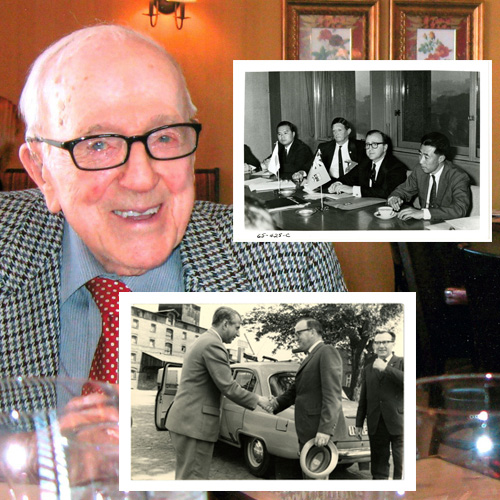

His boyhood passion turned into a breeding business that served international markets and established him as a top agriculturalist. By the 1970s, his company, Shaver Poultry Breeding Farms Ltd., licensed and distributed breeding stock to nearly 100 countries, and supported global organizations looking to produce more food in developing nations.

Long retired, he hasn’t raised poultry for a while, but that boyhood passion still lies near the surface for Shaver, who will turn 94 this summer. Near the end of an hour-long interview in his Cambridge retirement home, he quips, “I sometimes think of getting a little incubator in here.”

Several of his poultry lines do live on. To find them, drive a half-hour down the road to Guelph.

At the Arkell Research Station run by U of G, one long, low – and raucous – barn is home to breeding stock donated by Shaver to the University about a decade ago. Hand-selected for their breeding and production potential, these lines are pure strains of four types of poultry: barred rocks, white leghorns, Rhode Island reds and Plymouth rocks.

Today U of G students look after the birds, choosing and breeding the best each year to maintain their purity.

For Theresa “TJ” Williams, a fourth-year animal biology student, and Kayla Price, completing her PhD in pathobiology, the “Shaver barn” is more than an oversized chicken coop. Along with some 100 members of the U of G Poultry Club, they help maintain the birds, doing everything from feeding and watering the flock to breeding the birds and raising the next generation to maturity.

In one sense, the barn’s occupants are a closed reproductive loop, maintaining the best lines from one generation to the next. But they’re also a living library of heritage genes that might one day help breeders and producers boost egg production or thwart some yet-unimagined disease epidemic threatening global poultry stocks.

Today’s multimillion-dollar poultry industry worldwide is massive but precarious, says Prof. Gregoy Bedecarrats, Animal and Poultry Science. A physiologist at Guelph since 2003, he’s among scientists from three U of G colleges who are participants in a national poultry science cluster that received $5.6 million this year in federal and industry funding to study food safety and environmental aspects of poultry production.

So integrated has poultry production become over recent decades, says Bedecarrats, that “only two or three major breeders worldwide hold the entire genetics of the poultry business. That’s potentially dangerous. If anything were to happen to any of these super-concentrated worldwide lines, it could totally disrupt the supply chain of poultry worldwide.”

Call the Arkell gene lines a form of insurance against potential catastrophic failure of that industry, says Price, current president of the poultry club. Breeders and producers might turn to the reproductive loop at Arkell – and its genetic and production flexibility – to help restore a breeding population whose genes lend resistance to that potential epidemic.

“They’re a backup,” says Price. Adds Williams, those poultry genes are “a great resource to go back to if needed.”

As the poultry club’s junior breeding co-ordinator, Williams oversees the annual cycle of breeding and selecting birds to perpetuate the Arkell lines. Each year’s crop of new chicks goes to the “brooder barn.” That’s one of two Arkell barns that house several thousand commercial birds used in research projects, including initiatives within that poultry science cluster.

Bedecarrats, for instance, studies low-energy LED light bulbs to improve commercial egg-laying. Other researchers in his department such as Prof. Tina Widowski look at animal welfare issues.

At 18 weeks, the birds are moved to the “adult barn” next door. There the next breeding birds are chosen to produce the next generation. Each year, club members choose about 180 hens from each of the four lines and about 60 roosters per line for breeding. The students work with full-time staff members maintaining the flocks at Arkell.

Breeding occurs by artificial insemination over four or five weeks through late February and March, yielding thousands of eggs bound for incubators. The chicks hatch after 21 days of incubation.

Williams and other club members look for various traits at different stages, including egg colour, high fertility and hatchability, and well-formed chicks. Shaver last took part in that process during a visit to Arkell about three years ago.

It was his developing passion that brought him to Guelph – and the Ontario Agricultural College (OAC) – decades earlier. Shaver didn’t do degree studies here. As a youngster, he learned about husbandry mostly by reading. By his mid-teens he tended up to 200 chickens and won competitions for high-production layers. His flock hatched out hundreds of chicks each week during breeding season, which he sold to other producers. “Breeding seemed to come naturally,” he says.

For one week each summer, he cycled daily along the then gravel road to OAC for a poultry-rearing course taught by Prof. W.R. Graham. Graham began poultry science courses at Guelph in the early 1900s. The first poultry building – now called Graham Hall – was home to the poultry department from 1914 to 1969. For decades, chicken coops stood in a field behind that building.

The animal and poultry science departments combined in 1969 in the newly built Animal Science and Nutrition Building. Poultry production was moved to Arkell in 1975.

Shaver spent the Second World War as an officer with a tank corps in Europe. He saw devastation all around him in Italy and Holland, but he also saw future opportunity in animal husbandry, especially poultry. “It would have to be rebuilt. That gave me an international view.”

Back in Canada by early 1946, he started tending chickens again. A year later, he was breeding birds; he began exporting breeding stock a decade later. “They came from the best breeders of the day in Canada and the United States. Those farmers didn’t think I was a threat to them, so I was able to buy good lines.”

But there was more to successful production than sustaining good lines, he says. “They were good breeders, but one by one they went out of business because they were not adapting to the new selection procedures.”

Shaver worked with geneticists and with federal government officials, feeding information about his pedigree lines for computer analysis and using results to improve his breeding program. When he started, there were more than 250 poultry breeders in Canada. By the late 1950s, most had gone out of business or been bought out by international concerns. “In the end I was the only one,” says Shaver.

His days with the tank corps taught him the value of a backup plan. Today he views those lines at Arkell as just that: part of a Plan B for sustaining our global poultry population and for feeding the world.

“The great advantage of the Arkell program is that it’s being reproduced each generation by 70 males and 180 females per line,” he says. “They will only be recognized when we have a catastrophe, most likely lack of resistance to some new epidemic that could wipe out our highly selected population.”

Shaver sold his company in 1985. Two years earlier, he had become a director of the Canada Development Investment Corp.; he chaired the organization for 12 years.

Only minutes into a recent interview, he’s discussing global food production challenges. How to feed a world population that will reach an estimated nine billion mouths by about 2050, he says.

Shaver foresees competition between humans and livestock for increasingly scarce resources.

Add in growing concerns about our water supply, including drought conditions in some of the world’s most fertile areas. “Water being used is a greater influence on our future than oil.”

Shaver says poultry production is both part of the problem and part of the solution. Raising chickens around the world consumes numerous resources. In turn, producers look to extend the laying period. Currently, top laying hens can produce between 300 and 400 eggs in a season; producers are aiming for about 500. That will require birds to use nutrients more efficiently.

Considered a leader in increasing food production efficiency in Canada and abroad, Shaver was named a Member of the Order of Canada in 1978. In 1990, he became an Officer of the Order of Canada. He was inducted into the Canadian Agricultural Hall of Fame in 1987 and received honorary science degrees from U of G, McGill University and the University of Alberta.

Shaver received the OAC Centennial Award and served as the first U of G entrepreneur-in-residence from 1985 to 1987. A long-time U of G donor, he served on the Board of Governors and the Heritage Trust.

Note: Learn more about Shaver Poultry Breeding Farms in the Donald Shaver collection held in McLachlan Library, Archival and Special Collections.