Talk about all-consuming work. One day at the campus Brass Taps, Chris Weland had finished off all but a piece of his kangaroo burger. Curious about the menu item, he took that morsel back to the Biodiversity Institute of Ontario (BIO) across campus. There, he ran it through DNA barcoding analysis to verify the species.

Sure enough, the menu checked out.

His test found the burger contained mixed genetic signatures for wallaby and wallaroo. That was close enough for the BIO’s forensic analyst. “It’s from the kangaroo family,” says Weland.

He figures he’s the only forensics specialist in Canada using DNA barcoding specifically, as opposed to other kinds of genetic tests used in forensics cases. He returned to his alma mater in 2010, following more than a dozen years in criminal forensics work that included such high-profile cases as the Bernardo murders and the Swissair disaster.

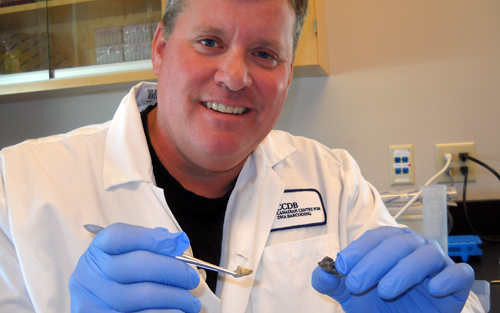

Among a growing roster of experts employed in the BIO’s Canadian Centre for DNA Barcoding (CCDB), it’s Weland whose job comes closest to something resembling the CSI TV series. Working behind the scenes, he and forensics lab technician Janet Topan routinely use Guelph-developed genetic testing to identify animal species worldwide.

Often, their testing for a telltale snippet of DNA peculiar to every living species helps to verify food claims – a growing market for barcoding experts. That technology was developed here by integrative biology professor and BIO director Paul Hebert. Says Weland: “I’m an application of Paul’s brainchild.”

Their work made North American headlines earlier this year about mislabelling of nearly one-third of seafood sold in grocery stores and restaurants in the United States. That was the largest seafood fraud study of its kind.

But that’s only one example. Ask Weland about his investigations this year alone, and he plucks a handful of orange file folders from a shelf. Leafing through the pile, he rhymes off recent cases.

In one, a suspect had been charged by Toronto police for having killed a dog. Testing at the CCDB matched the animal species with blood on a hammer. The suspect confessed.

Another file involved a Florida doctor who wanted to verify the contents of a hamburger patty. Testing confirmed the meat was 100-per-cent Bos taurus beef.

How about these cryptic insect larvae sent in by Canadian researchers? Could the CCDB identify the species? Indeed, says Weland: Indian meal moth.

There’s no shortage of cases to work on – anywhere from three to 10 at a time. Sometimes those cases overlap with the BIO’s research goal of cataloguing all life on Earth.

That bit of kangaroo burger also pointed out a gap in the growing CCDB library. In testing his lunch, Weland learned that four key species of the signature Australian marsupial – red, eastern and western grey, and antilopine kangaroos – had been missing from the reference database. Since then, the lab has generated barcodes for eastern and western greys from Winnipeg and Toronto zoos, and is working on the other species.

The kangaroo meat query also led the CCDB on another investigative path.

Earlier, European media had run stories about horsemeat found in hamburger patties and frozen lasagna. Would Canadian hamburgers pass muster?

Testing at the BIO gave passing marks to 15 cooked and frozen burger samples. From McDonald’s to Burger King to Wendy’s, all samples contained beef in a study that also garnered national and international headlines earlier this year.

BIO forensic experts are now using barcoding to identify animal species in processed meats supplied to a multinational retailer.

Besides doing hands-on barcoding, Weland would testify in criminal court cases – a role he got used to in his earlier jobs.

During 13 years spent in criminal forensics, he was subpoenaed to provide evidence hundreds of times. He worked first for the Centre of Forensic Sciences in Toronto and then at Maxxam Analytics Inc. in Guelph.

At the latter – a full-service analytical testing laboratory – he helped to set up the forensics lab and procedures, and generated more than 50,000 human forensic DNA profiles for RCMP criminal cases. He’s trained in autopsies and in identifying bodily fluids at crime scenes.

Among his major cases, Weland worked on evidence stemming from Paul Bernardo’s 1995 murder trial and helped ID victims of the 1998 Swissair plane crash near Peggy’s Cove, N.S., that killed 229 people.

Once, he visited Dawson City in Yukon for an exhumation – “I was on a shovel,” he says – to establish parentage in an estate dispute. He was unable to make a decisive match: “That’s forensics: you never know when it’s going to work out.”

Called to examine evidence after a sexual assault in Alberta, he says, “I got the DNA profile off the belt of a girl and got a match.” That evidence helped convict the offender.

He’s also been called to help identify spices – cumin, curry powder – used to mask clandestine substances. That client was the U.S Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives.

Weland has worked on cases for the Ontario Provincial Police and municipal police forces, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, Environment Canada, the federal Department of Fisheries and Oceans, the Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources and numerous private companies.

He’s even profiled human feet and heads washed up on Canada’s east and west coasts.

Criminal forensics requires mental toughness, says Weland.

Although he often knew the details of cases – homicides, rapes, sexual assaults, burglaries – he says, “I just shut it out and did the work. You don’t think a lot about it. You just do the best you can from the DNA.”

Still, he was heading for burnout. “After 15 years, I had to get out. Working 80 to 120 hours a week kills your quality of life.”

Coming to Guelph three years ago was a homecoming of sorts. He had completed his undergrad in fisheries biology here in 1996 after finishing a math degree from the University of Waterloo.

Weland studied fish genetics with integrative biology professors Moira Ferguson and Roy Danzmann. Today, he says he’s back where he belongs.

He’s even got a new fish barcoding project on the go, one that he calls a “game-changer” for conservationists and resource managers.

He’s also working with Profs. Kevin McCann, Integrative Biology, and Neil Rooney, School of Environmental Sciences, on a project in Georgian Bay. They’re combining barcoding and stable isotope analysis to assess aquatic environments.