At Guelph presents this story as part of a series that highlights University of Guelph leadership in teaching excellence and the scholarship of learning.

“Teaching is more than a profession for me; it’s a passion,” says physics professor Martin Williams. It comes as no surprise that his students nominated him for the Central Student Association’s Teaching Excellence Award, which he received this year.

“Of course I paid them lots of money to say nice things about me,” he says with a laugh, which is quickly followed by a more humble comment. “There are a lot of professors at the University who I think are more deserving of this.”

At the beginning of each term, Williams gives his students an important rule to follow. “There are two words that you should never mention to me in the same sentence if you ever want to pass this course. Those two words are ‘Manchester’ and ‘United,’” he says, pointing to the Liverpool flag displayed prominently on his office wall. He uses this pseudo-threat to create a more relaxed atmosphere in his classes and help his students feel comfortable about approaching him with questions.

“Physics has an image problem which I think is not fair,” says Williams. With up to 600 students in his classes, keeping them engaged is one of his biggest challenges. That’s why he breaks up each lecture with interactive demonstrations and discussions.

One of his favourite demonstrations is called the “monkey hunter” in which a scientist tries to shoot a tranquilizer dart at a monkey hanging from a tree branch. As soon as the scientist pulls the trigger, the monkey lets go of the branch to escape. The students have to predict what happens next: does the monkey escape or does it get hit by the dart?

Williams simulates the demonstration in his class using a ball bearing to represent the tranquilizer dart and a can for the monkey. Four years after one of those demonstrations, a former student told him that he still remembers the intense discussion that followed during class and later that day with his roommates in residence.

Williams also uses i-clicker technology as a learning tool in his lectures. “It gives me instant feedback as to how students are performing, as well as facilitating a student-centred, active learning classroom,” he says. “If 90 per cent of the class gets the question right, then obviously they understand the concept.” But such a high percentage of correct answers may also mean the students aren’t being challenged enough, he adds.

That’s why he prefers to ask questions that result in a cross-section of answers. “I like to choose a question that’s always challenging. What I want to see is that 20 per cent voted ‘A,’ 30 per cent voted ‘B’, 10 per cent voted ‘C.’ I want to see a multiple selection of answers.” That range of answers allows students to learn from each other.

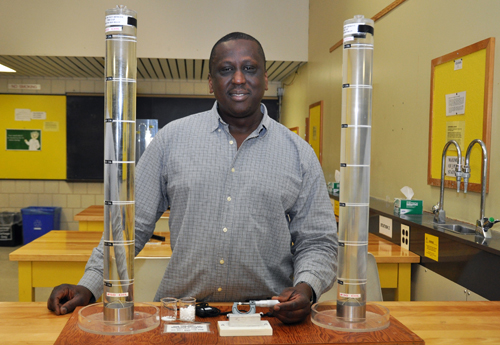

Williams often gives his students a scientific scenario to ponder, such as the common misconception that heavier objects fall faster than lighter ones. “In principle all things fall at the same speed if there is no air resistance,” says Williams. “If you remove that variable of air resistance, then all things fall at the same speed.” Showing students this concept in a demonstration is more effective than just telling them, he adds, because students are more likely to remember something they witnessed than heard. Using two objects with different weights, he asks students which object will fall faster.

They submit their answers using clickers, but he doesn’t show them the results of the first vote until after he asks them to “pair and share” (discuss their answers with their classmates). “Peer learning — students teaching each other — is the most effective and efficient way for students to learn,” says Williams. When the students submit their answers a second time — after consulting with each other — he shows them the results of both polls. “The answer ‘B’ will move from 30 per cent to 80 per cent in a two-minute period. What it seems to suggest is that somehow that 30 per cent has managed to teach 50 per cent of the class.”