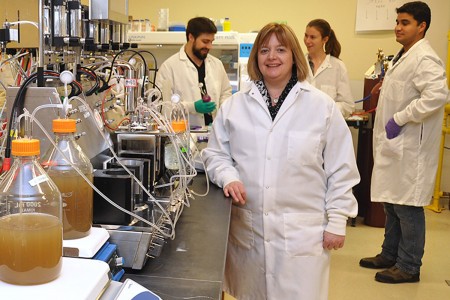

The secret to saving the lives of some vulnerable preterm babies may be in their poop. University of Guelph professor Emma Allen-Vercoe, Department of Molecular and Cellular Biology, is using stool samples from preterm infants and the “robo-gut” in her lab to uncover the causes of necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC), a life-threatening illness.

The secret to saving the lives of some vulnerable preterm babies may be in their poop. University of Guelph professor Emma Allen-Vercoe, Department of Molecular and Cellular Biology, is using stool samples from preterm infants and the “robo-gut” in her lab to uncover the causes of necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC), a life-threatening illness.

About 12 per cent of preterm babies will become sick with NEC, and of those more than 30 per cent will die, according to a study in Advanced Neonatal Care. Those who survive may have lifelong problems. Because the disease is so serious, finding the cause — and a cure — has been a goal for many researchers.

Early studies were disappointing because the disease couldn’t be linked to a specific germ. But Allen-Vercoe says that’s not surprising.

“Many of the diseases we are looking at now have more to do with how the microbes are behaving under a specific set of environmental conditions — for example, different diets,” she says. “The key is to discover what in the environment is causing them to behave badly.”

She’s collaborating with a neonatologist from the University of Chicago, who has taken stool samples from healthy preterm babies and identified which ones developed NEC and which babies didn’t. The researchers are also using samples from Toronto’s Hospital for Sick Children.

The neonatologist could identify the microbes in the stool, but nothing more. That’s when she reached out to Allen-Vercoe.

“Here we can actually culture the microbes and feed them in the robo-gut,” says Allen-Vercoe, whose U of G lab focuses on the study of normal human gut microflora, both in disease and in healthy conditions.

The robo-gut is a piece of laboratory equipment that mimics the environment in the lower intestines, allowing researchers to see what happens when food or medications are added to the stool sample. Working together with PhD student Sandi Yen, Allen-Vercoe is adapting this model to mimic the particular conditions of the premature infant gut.

Earlier studies have shown that when preterm babies are exclusively fed human milk, their risk of NEC is very low. Allen-Vercoe explains that human milk supports the microbes in the gut to produce the right metabolites. “There are components in human milk that are targeted to specific beneficial microbes,” she says.

Current testing is using the special formulas fed to at-risk newborns in hospital. Allen-Vercoe has fine-tuned the robo-gut to match the slow digestion rate of the preterm baby. She found the current formula feed yields excessive protein, which causes the microbes to react by fermenting the protein. If the model is correct, this could be a potential problem for premature infants, since the products of protein fermentation are often harmful metabolites.

In addition to studying the effects of different types of feedings, Allen-Vercoe is assessing the effects of antibiotics on babies’ gut microbes. Most preterm babies are administered antibiotics, but she obtained a stool sample from a baby who didn’t receive them. “We treat that poop like gold,” she says. This will allow Allen-Vercoe to study how antibiotics change the microbes’ behaviour.

“If we can understand what is causing NEC, we can guard against it and potentially save the lives of many babies,” she says.