Got butterflies in your stomach? Prof. Emma Allen-Vercoe, Molecular and Cellular Biology, is using another kind of bug to study how stress affects the gut and help doctors treat inflammatory bowel disease (IBD).

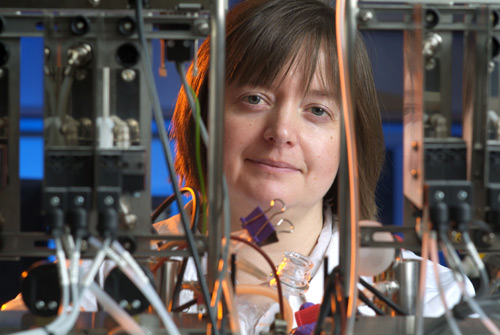

To do that, she’s assembled something in Guelph’s science complex that you won’t find on too many lab benches in Canada. All gleaming stainless steel and glassware, the “robo-gut” doesn’t look much like human innards. But by mimicking the environment of the large intestine, this new equipment will allow the microbiologist to learn more about the hundreds of bacterial species that aid in normal digestion and absorption of nutrients. More than that, the setup will enable her to investigate what goes wrong in people with ulcerative colitis, a form of IBD.

About 200,000 Canadians have IBD, including almost 90,000 with ulcerative colitis. There’s no cure for IBD, which costs Canada an estimated $1.8 billion a year in medical and indirect costs.

Ulcerative colitis causes inflammation and ulcers in the lining of the colon and rectum. Although researchers don’t know what causes the disease, they know that stress can trigger or worsen symptoms.

Allen-Vercoe, who receives research funding from the Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation of Canada and from the Canadian Institutes for Health Research, is studying the role of the stress hormone norepinephrine. Other scientists have added the hormone to E. coli cultures and seen effects on various bacterial genes. She has replicated those experiments in bacterial communities using the robo-gut, but she’s interested less in specific genetic changes and more in epinephrine’s effects on the intestinal microflora.

Compared with a control sample, the hormone caused noticeable changes in numbers and kinds of species of bacteria. Allen-Vercoe likens the effects to what can happen in a larger ecosystem on Earth. “If it’s a healthy rainforest, and you throw in some perturbation, the ecosystem adapts. But if you start stripping out species and throw stress in, the ecosystem collapses.” Bacterial diversity in the colon is known to decrease in people with ulcerative colitis.

So far, she’s used samples only from healthy people. Now she plans to work with Dr. Naoki Chiba, a Guelph gastroenterologist who will provide stool samples from his patients at the Surrey GI Clinic.

“We’re trying to understand the disease better so that hopefully we can target treatment for it down the road,” says Chiba. “We don’t have a cure for the disease.”

Technically, the U of G setup is called a chemostat, a bench top-sized bioreactor that maintains micro-organisms in an airless environment like that of bacteria living in the colon. Equipped with pumps, probes and gas lines that keep the system going under computer control, the robo-gut consists of six glass flasks that allow her to vary experimental parameters.

Each flask holds about two cups of liquid distilled from stool samples containing the gut bugs. Says Allen-Vercoe: “You don’t want any more than that because it’s pretty disgusting to clean up.”

Much of the hands-on work involves master’s student Julie McDonald, a former summer student in the lab who completed her B.Sc. in 2009. Acknowledging that acquaintances are often taken aback by what her supervisor calls the “poopy lab,” McDonald says she’s fascinated by that intricate ecosystem inside us.

“There’s so much we don’t know. We’re not just focusing on one bug but on a community,” she says.

Allen-Vercoe is beginning a new project on intestinal biofilms, mats of micro-organisms that can become a health hazard in human organs. With colleague Prof. Cezar Khursigara, she plans to test the idea that biofilms might provide a haven for good bugs in the gut, allowing the GI tract to restore normal intestinal flora after severe diarrhea and other diseases.

She’s also using her new lab setup to continue growing and isolating novel gut bacteria, including species previously thought to resist culturing. She contributes to Canadian and global projects in which researchers are sequencing bacterial genomes to learn more about microbes’ role in health and disease. And working with researchers at other Ontario universities, Allen-Vercoe plans to study possible links between gut bacteria and diseases affecting the brain.